Transmedia Engagement: Creating Compelling, Immersive Experiences

Technological developments continually offer storytellers new delivery, connection and sharing options. Each choice raises an equal number of questions, from financial to design considerations, that are both exciting and burdensome. While audience expectations and demands materially change with each shift in technology, the increasing complexity gravitates attention toward the producer.

The wide array of new technologies allows audiences to be more discerning about how they allocate their time as consumption is limited by hours in the day. The psychological implications of “choice” are wreaking havoc leaving media businesses and producers scrambling for a cure. Transmedia storytelling has emerged as a means of addressing the competition for attention and expanding the breadth of access as well as satisfying audience demands for personal control, feedback, interactivity, and social connection integrated into media experience.

Technology changes expectations, but it does not change fundamental needs and motivations. In meaningful ways, people are the same as they have been for thousands of years, driven by instinct and emotion. This includes the drive for social connection, meaningful experience and sharing stories to be part of something larger than themselves.

Everyone has a story. Stories are how humans construct identity, make sense of the past, anticipate the future and find the motivation to take action (McAdams 2013). The increased sense of empowerment derived from digital technologies and the proliferation of media options has been accompanied by a desire for increased personal meaning in media experiences. The trend towards transmedia storytelling is well positioned as it can offer richer, more immersive and meaningful experiences by marrying consumption with participation. To satisfy audience demands, transmedia does not have to be a fully-built-out, multi-platform, mega budget storyworld, like the iconic entertainment franchises surrounding Avatar or Star Wars. Effective transmedia storytelling embraces the storied nature of life where multidimensionality, sociality and interactivity are core features. Transmedia storytelling replicates human experience in how people naturally interact with their worlds and, at a neural level, in how brains process information and transform sensory input into conscious experience.

Pushing Boundaries

Transmedia continues to push the boundaries of storytelling through the use of multiple platforms and technologies that expand stories from singular linear narratives to multidimensional user experiences. It also, by necessity, disrupts traditional approaches to experience design with the complexity of creating holistic story experiences in danger of overshadowing the need to create sustainable audience engagement across texts.

The psychology of transmedia design is at the root of successful engagement in a storyworld through the experience of immersion and presence across multiple mediated experiences. Presence is an affective-cognitive construct characterized by the sensation of “being there” and describes an audience’s perceived connection with a story (Gerrig 1993). Presence lowers cognitive resistance, making the audience more likely to suspend disbelief. In pursuit of presence, producers increasingly integrate the rich technology-enabled content such as augmented and virtual realities. But technology without psychology is a double-edged sword. Presence may come at the cost of decreased usability, narrative confusion or reluctance to adopt new technologies.

To create a seamless experience across platforms, producers must adapt to new technology guided by psychological implications. They need a way to make judgments about which elements will add value to user experience at a fundamental level and which may detract.

Psychology Shifts the Focus

Findings in neuroscience, cognition, and perception combined with theories of optimal engagement and narrative transportation provide an integrative framework to evaluate the potential for immersion and engagement in and across new technologies. This approach enables creators to shift from a production-focused paradigm to a more user-centric one. This allows the integration of basic subconscious functions such as attention, perception and cognitive heuristics, with conscious meaning-based processes such as enjoyment, flow and social connection.

The link between psychology and project execution is especially important for transmedia storytelling because, by definition, the orchestration of elements relies heavily on understanding audience behavior. Success rests on the ability to support audience engagement from the initial connection with the story to migration across media. Transmedia’s complexity can easily focus the emphasis on development over consumption. However, as transmedia producer Andrea Phillips (2012) notes, this preoccupation is problematic. To be successful, transmedia cannot assume the audience will appear, but needs a structure that entices, engages and guides the audience at several junctures.

Producer Decision Points and User Experience

To expand a story into a story world, producers face a number of decision points—all with potential psychological consequences and commensurate moments of choice for the audience. While multiple media properties allow a well-crafted storyworld to take on rich dimensions, they require a greater commitment and motivational level from the audience to pursue the story beyond a single linear experience. The producer must decide not just how to tell the story but whether the myriad of potential choices, such as media assets, platforms, activities, and back or side stories, will enhance or disrupt the overall narrative coherence and the ability and desire of the audience to stay engaged.

User experience (UX) has been used as an umbrella term for a wide variety of human-media-technology interactions, yet transmedia migration is seldom one of them. Though the fields of human-computer interaction (HCI) and UX are rooted in cognitive psychology, the qualitative experience of storytelling, meaning-making, identity, and efficacy are uncommon (Petrie and Bevan 2009). While emerging as a usability tool, such as in persona development, they are not the driver of the overall experience. In HCI and UX, users have stories, but users are not in the story. In transmedia, the opposite is true. The audience is in the story, but audience members are rarely acknowledged to have stories of their own. Yet, most transmedia relies on discoverability, ease of use and the affordances of different technologies, as well as audience preferences and needs. The ABC television show Lost had an extended storyworld across multiple platforms, such as mini webisodes, maps, blog, references sites and a video game. All are instances where audience-centric issues would be a factor in access and narrative experience that could ultimately constrain audience reach and, by extension, impact the user-generated content that played a role in Lost’s success.

Mapping transmedia experiences to psychological impact forces an examination of “why” from the perspective of both the creator and the audience. It focuses on how the story, structure and distribution platforms are intended to engage different psychological processes and forces the articulation of expected outcomes. Deconstruction of transmedia is counter-intuitive in that it is the synergy among the texts that creates the immersive and often magical experience of a good transmedia story. The parts cannot reflect the richness of the whole. The parts do not capture the sensation of breadth in a storyworld like Game of Thrones, the shifting attitudes toward teen pregnancy and reproductive health due to Hulu’s East Los High or the poignant complexity of teen depression and suicide in Netflix’ 13 Reasons Why. This ability to amplify and broaden experience is transmedia storytelling’s strength. However, the effect is reliant on activating individual elements that, taken together, create the sense of immersion that defines the audience’s journey.

Psychological Foundations of Transmedia

A critical feature of the psychological theory behind transmedia is the interrelationship of unconscious and conscious processing. The integration of sensory stimuli in the human brain with conscious understanding of experience plays an important role in creating and sustaining engagement. Engagement can have many practical definitions depending upon project goals, from sustained attention to specific actions.

At the most basic level, engagement begins in the unconscious, with attention to sensory stimuli. The brain ultimately translates sensory input into conscious meaning in the context of an individual’s previous experiences and beliefs. The multi-dimensionality of transmedia implies a continued shifting of attention and meaning-making, synthesized into a whole to achieve a level of engagement across texts. Thus, a transmedia experience, and the potential for sustained engagement, continually evolves as stimuli change.

The transmedia experience, therefore, can be tracked from sensory triggers that initiate attention through the conscious and unconscious impact of storytelling to the motivational dynamics of narrative and structure in transmedia migration.

The following are the critical points in this journey:

- Attention precedes audience engagement and is the product of instinctive processing.

- Social connection is a primary human goal and is central to the survival instinct.

- Humans exhibit a biological preference for real over virtual, however, both virtual and physical stimuli activate identical unconscious arousal responses. This response directs attention and is responsible for the ability to respond to an activity or action as relevant, desirable, valuable, pleasurable or the opposite.

- Instinct and emotion subconsciously dominate the decision-making process.

- The brain processes all information using narrative structure as the sorting device to organize and link multisensory perceptions and meaning for later recall

- Narrative as a theory of mind makes making storytelling fundamental to all human communication.

- A user’s ability to achieve engagement relies on a producer’s skill in understanding principles of sensory perception, emotion and narrative processing.

- Neural networks, information processing and encoding patterns enable narrative experience with or without overt storylines.

- Narrative is the universal factor enabling the “suspension of disbelief” that underlies psychological immersion.

- The ability to experience presence or to feel transported into a narrative can occur whenever a mediated experience triggers emotion and imagination.

- Presence and narrative transportation allow a narrative to become part of the audience’s identity and personal story.

- The narrative zone is a construct describing the experience of being in a narrative.

- Theories of narrative transportation, flow and presence define the boundary parameters that keep the audience in a narrative zone or storyworld.

- Flow and transportation theories are not interchangeable. They differ in the relative engagement of conscious to unconscious processing.

- Task-based actions that generate flow require higher consciously directed focus compared to narrative-based experiences that place more demand on unconscious processing, such as emotion and visualization to fuel sense of presence.

- Sustained engagement, as described by both flow and transportation theories, requires the balanced coordination of conscious and subconscious processing albeit to different degrees.

Attention Starts in the Brain

The critical component for transmedia storytelling is engagement—the ability to attract and keep attention. All physical and psychological experience, including the ability to notice and attend, is first filtered and then constructed by subconscious sensory processing systems, therefore persuasion, as the outcome of attention, starts in the brain.

The brain processes new information based on the survival imperative and gathers multi-sensory input to evaluate relevance, novelty (movement, newness, unusual behaviors), and pattern comparison (familiarity, sense-making) to determine the potential for threat or reward. Conscious attention is the result of unconscious arousal that occurs in response to the “pain or gain” threshold (Rutledge 2012).

Once information triggers attention mechanisms, cognitive processing continues by comparing new information to previous experience to determine the level of reward or threat. Content that is perceived as a reward will engage conscious processing to evaluate the positive potential. Research demonstrates that information that is both relevant to the user’s goal and consistent with or enhancing the user’s sense of self heightens the perception of value and motivates further attention. Continued attention creates concentration which increases the probability of liking. The ability to self-reference and self-identify promotes a favorable evaluation no matter what the quality of content logic or information (Escalas 2007).

Using the Triune Brain Heuristic in Transmedia Design

Insights drawn from neuroscience provide a valuable lens for transmedia design decisions and post mortem analysis of previous projects. A modular concept of the human brain was proposed by neuroscientist Paul D. MacLean in the 1960s. It continues to provide a simple approach to conceptualize and anticipate the impulsive and often unpredictable nature of human behavior and is widely applied in fields of neuromarketing and neuroleadership.

In the Triune Brain theory, MacLean proposed that people process information in three ways: instinctively, emotionally, and cognitively via separate brain centers that map to the acknowledged stages of evolutionary development of the human brain. These are the primitive or instinctive brain, the limbic system or emotional brain and most recent from an evolutionary perspective, the neo-cortex or rational brain (MacLean 1990).

The order of dominance in message processing has a profound impact on interpretation and response. Emotions are the functional directors of the neural interactions that govern attention and meaning, from perception to inference and goal choice (Reiner 1990). Therefore, instinct and emotion frequently drive behaviors. Unconscious instincts and emotions not only control reactive responses, but evidence suggests that as much as 95% of decision-making is based on instinct and emotion and is later rationalized by the conscious brain to align desires with conscious meaning. This predisposition is frequently exploited by marketers who link primal drivers of emotional arousal such as sex and rejection with congruent products.

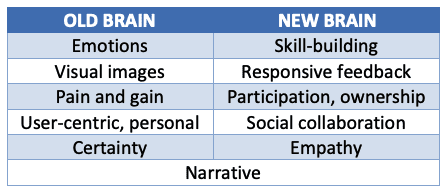

The triune brain theory is a practical hierarchical framework for anticipating how content and structural choices will be received and what behavioral responses can be anticipated. Great content will not offset consumer frustration over poor user interface design because negative emotions trigger the instinctive responses of fight or flight, resulting in avoidance and distancing behaviors. Conversely, offering rewards of prizes or appreciation can increase a consumer’s tolerance of difficulty because positive emotions enhance trust and liking. Content that is difficult to understand or find or that activates self-consciousness or self-doubt increases demands on conscious cognitive processing and impedes hedonic enjoyment (Barasch, Diehl, and Zauberman 2014). As indicated in Table 1, different attributes activate different brain functions. However, the critical rule of thumb is that instinct and emotion take precedent.

Table 1. The Triune Brain Theory highlights the three pathways of experience processing: lower level processing such as instinct and emotion and higher level, conscious processing that creates directed attention and meaning. Narrative is uniquely able to bridge all three, facilitating immersion and persuasion.

The Psychology of Story

Transmedia producers are well familiar with the nuts and bolts of storytelling since the foundation of transmedia is a good story. In cases such as entertainment properties that are anchored around a movie franchise like Pirates of the Caribbean, the story is well developed and articulated with accuracy and consistency across a number of media, such as books, video games and even amusement park rides. In other cases, the storyworld is defined largely within the consumer’s brain. This is most common in brand stories. Apple, for example, has created a clearly defined brand storyworld based on the celebration of individualism, creativity and innovation that is demonstrated and reinforced emotionally by all customer touchpoints from package design, advertising campaigns and product functionality to store design, sales personnel training and the Genius bar. Chipotle Mexican Grill has also developed a brand story that is far more than that of a “Mexican fast food restaurant.” The food genre is almost incidental to the brand story of social responsibility emphasized in the “food with integrity” tag line. Chipotle maintains story coherence across the restaurant experience and advertisements, and demonstrates their larger purpose through support of community fundraisers, sponsoring local farms, and the slow food movement. Chipotle has successfully amplified their brand story and expanded their reach, urging the audience to “cultivate a better world” with animated advocacy videos such as Back to the Start and Chipotle the Scarecrow, an accompanying free arcade-style adventure game for mobile devices, and even a satire Hulu TV series Farmed and Dangerous. In Apple’s and Chipotle’s storyworlds, consumers are the hero. As in any powerful story, the hero is transformed enabling customers to rewrite their personal stories and embrace aspirational identities.

The Brain Fills in Gaps

Transmedia storytelling campaigns benefit from the predisposition of the human brain to use narrative to facilitate meaning-making. As illustrated by Apple and Chipotle, a storyworld does not need to be fully articulated. Narrative is the native language of the brain and people are unconsciously motivated to make sense of information by organizing it as a story (Haven 2007). When stories are incomplete or information unavailable, the audience will infer connections, motives and significance to achieve a sense of narrative logic (Bruner 1991). The “gaps” in brand stories make room for consumers to insert themselves, increasing brand salience. By definition, transmedia relies on the audience to insert themselves through sharing and user-generated content (UGC). The psychological UGC, the invisible byproduct of the interaction between the consumer and the mental process of meaning making, goes unacknowledged.

The gestalt principles of perception demonstrate how the brain attributes meaning to information, assigning hierarchy, movement, dimension and intentionality to visual objects based on their colors, relative sizes, location and perceptions of movement (O’Connor 2015). This attribution of meaning is not restricted to visual information. The brain fills in the gaps and assigns relationships to all information using a narrative organizing structure that enables sequencing and extrapolations of causality. This ability to complete patterns, make judgments and infer actions is an innate tendency essential to human survival. It not only drives the propensity to anticipate story endings, it is at the root of a number of cognitive heuristics that inform decision making.

Decisions are the product of needs moving toward goals. Contrary to popular beliefs, human needs are not hierarchical (Rutledge 2012). Social neuroscience has confirmed earlier work on attachment and motivation and shown that social connection is fundamental to human physical and emotional survival (Lieberman 2013). Thus, storytelling, as a social activity, is not just an entertaining pastime. It defines what it means to be human. It is a core skill that moves a need toward a goal—human connection. In fact, storytelling is such a critical skill that the ability to tell stories is used as measure of cognitive development.

Stories serve many functions critical to human survival. They:

- provide the primary mode of meaning construction and transfer of understanding;

- enable the exchange abstract concepts;

- are a conduit for social norms and cultural transmission;

- allow assignations of significance and intention that are essential to achieving interpersonal connection and emotional intimacy.

All Stories Start as Chemical Signals

All information comes through the five senses—sight, touch, smell, taste and sound. Narrative structures enable the brain to translate, interpret and encode sensory input as conscious meaning. Internally, narratives provide the sequencing and multi-sensory links that facilitate understanding and recall and become the foundation of beliefs, schemas and mental models. The internalization of culturally-shared mental models and schemas defines salient individual and social identities and provides the textual, visual and auditory metaphors that storytellers can employ to effectively engage and motivate their listeners.

The implications of information processing suggest that storytellers should begin as listeners. The audience’s stories contain the beliefs, assumptions and metaphors that operate as filters and magnets, unconsciously influencing meaning and perceptions of relevance, authenticity and liking. Internal cognitive structures and schema create a myriad of expectations, from the practical, such as where content should be found or how to navigate a site, to the emotional, such as motivating the audience to migrate across texts.

Metaphors and Archetypes: Cognitive Patterns of Shared Meaning

The psychologist Carl Jung used the construct of archetypes to conceptualize personality development and motivation. To Jung, archetypes represented universally-shared primal forces in what he described as a collective unconscious. Jungian archetypes are patterns of human experience that create a common language for understanding life, people and behavior. In contrast to personality traits, archetypes are a constellation of profound qualities that are instantly recognizable across cultures and evoke deep emotions (Read, Fordham, and Adler 1959/2014). The resurgence of interest in storytelling has created an accompanying appreciation for the power of archetypes and their ability to encapsulate core concepts, social roles and behavioral attributes. Despite cultural variations, archetypal themes, settings, and characters embody essential elements of universal human experience that are identifiable across myth, literature, and rituals. Archetypal characters and themes feature prominently in the stories of well-known transmedia franchises, such as Star Wars, The Matrix, Avatar and The Hunger Games. They are equally powerful communication tools in brand stories. A clear and consistent archetype sends an instantly understandable signal about a company’s brand promise and correlates financially through strong brand equity and relationally through customer commitment fueled by a desire to belong (Mark and Pearson 2001). They are equally effective in focusing brand stories. Companies like Harley Davidson, Coca Cola and Disney have all benefited from the application of brand archetypes.

In storytelling, archetypes function as heuristics that deliver a large amount of meaning with relatively little information and effort. Archetypes tap into the audience’s preexisting knowledge and emotion and clearly communicate information about the characters. This instantly establishes expectations about plot, genre and action, increases identification with characters and enhances audience commitment through meaning construction (Woodside, Sood, and Miller 2008). Identification with characters has been shown to predict the emotional impact and enjoyment of media entertainment and to increase the persuasive effects of messaging (Zillmann and Vorderer 2000, Green and Brock 2002). In addition, archetypes allow the story to bridge the cognitive gaps between texts during migration because the audience implicitly understands the roles and intentionality of the characters, keeping the audience in the narrative zone.

Stories Link the Parts of the Brain

Stories evoke emotion and images, activating the instinctive brain while actively engaging cognition and meaning. In the Triune Brain framework, stories have the unique ability to bridge all levels of the brain, linking instinct, emotion with rational thought.

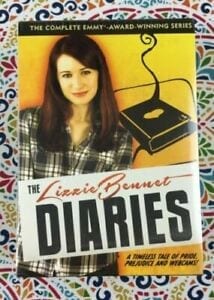

Case Study: The Lizzie Bennet Diaries

The Lizzie Bennet Diaries, the transmedia adaptation of Jane Austen’s classic story Pride and Prejudice, was hailed as an unqualified success due to its creativity and innovative approach. It is also a good case study to explore the psychological dynamics that can benefit transmedia.

Lizzie Bennet Diaries drew on a known and loved story and storyworld reinforced by archetypal characters. The ready fan base fueled expectations, familiarity and anticipation, increasing liking. Sequels and storyworld expansions of popular properties, such as Marvel Universe extensions, benefit similarly. The casting was consistent with known intentions of the characters; variations in side narratives aligned with current cultural metaphors, such as transforming Lizzie Bennet’s best friend, the industrious, practical Charlotte Lucas, into an entrepreneur.

Multiple platforms took advantage of affordances to enhance relational connections between audience and characters. For example, the vlog format allowed actors to speak directly to the audience. Conversational speech and using the camera to simulate the experience of eye contact triggers mirror neurons which collapses the distinction between real and virtual. This personalization was reinforced by adopting the within-family nickname for Elizabeth (Lizzie), a social convention that signals access and intimacy.

The characters were available to engage with the audience on multiple social media channels. Twitter, in particular, was successful at breaking the fourth wall and further amplifying the sense of unmediated and authentic connection. The lack of perceived mediation on Twitter facilitates the development of parasocial relationships where the audience begins to feel they actually know the characters and actors, increasing emotional commitment (Horton and Wohl 1956).

Audience participation enhanced ownership and buy-in to the project’s success, motivating people to share and encourage others to participate to maintain ego consonance. Comments, shares and unearned media provided social proof and validated the Lizzie Bennett Diaries, creating opportunities for affiliation as a fan or arbiter of something new and special (Cialdini 2007).

To celebrate the fifth anniversary of the original launch, the creators re-released all of the content in real time on Facebook; this not only extended the fan base but rewarded existing fans by letting them re-experience the series as it was originally launched. This type of event triggers the neural networks storing the multi-sensory memories and amplifying current experience with previous emotions and meanings.

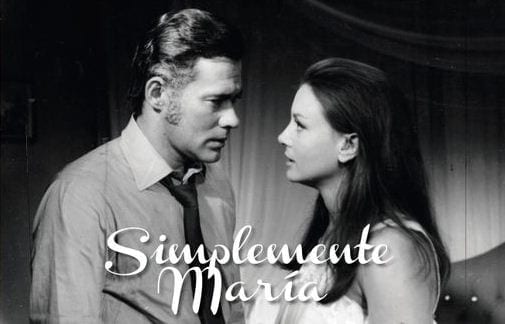

Case Study: Simplemente Maria

The 1969-70s, Peruvian telenovela, Simplemente Maria [Simply Maria], is an earlier example of how psychological dynamics can help propel a narrative. One of the longest running and most popular telenovelas in Latin America, it told the story of a young country girl who came to the city to find work and was seduced and abandoned. The audience lived Maria’s story over 448 episodes. They watched her struggle with the social stigma of having a child out of wedlock, overcome economic hardships by learning to read and sew and, ultimately, emerge triumphant in business and love. While the goal of the program was to provide commercially viable entertainment, unintended social consequences included a spike in the sales of Singer sewing machines and young housemaids across Peru emulating Maria’s behavior by enrolling in literacy programs (Singhal, Obregon, and Rogers 1995).

Like the Lizzie Bennett Diaries, Simplemente Maria drew on clear archetypal characters and themes. Maria was hardworking and idealistic despite challenges. Her Orphan (or Cinderella) archetype was placed in a culturally relevant story, reflecting the social struggles of the pressures from rural-to-urban migration in Peru at the time. Maria was relatable and aspirational; her success modeled a behavioral path and validated the hopes and efforts of many, reflecting, ultimately, the “just world” cognitive bias that good things should happen to good people (Dalbert 2004).

Simplemente Maria was also a harbinger of transmedia storytelling. Strong parasocial relationships developed in response to well-known and appealing characters and the frequency of television and concurrent radio broadcasts. Multiple distribution channels extended reach and access points and took advantage of the cultural habits of shared viewing and verbal discourse, increasing the retelling and psychological appropriation of content. Involvement was amplified by framing social and political issues in personal and familial terms around archetypal themes, increasing both salience and emotional participation.

Recognizing the power of subconscious drivers in programs like Simplemente Maria, Televisa executive Miguel Sabido was inspired to develop a theory-based approach to telenovela storytelling that would intentionally target social change. Drawing on experts in behavior change and communication, Sabido created a distinct methodology that was the basis for his productions, making him a pioneer in the Education-Entertainment genre. For over 25 years, he successfully produced media structured on psychological theory and achieved significant social impact, tackling topics from birth control and literacy to HIV testing (Papa et al. 2000).

The Sabido Methodology remains a model for the incorporation of psychological theory into media construction. It integrates: 1) dramatic theory to extend emotional range and increase attention and direct focus, 2) circular communication theories to capture the impact of messages and the renorming of beliefs reaffirmed by offline discussion and social sharing, 3) universals drawing on Jungian archetypes to trigger recognizable and relatable characters and plots and to enhance buy-in, 4) transitional characters to model a pathway for behavior change based on Albert Bandura’s social cognitive theory, 5) instinctive, emotional and cognitive triggers drawing on MacLean’s Triune Brain Theory, 6) enhanced personalization to promote parasocial relationships and 7) Sabido’s theory of tone which used sound variations to activate targeted somatic responses. The Sabido Methodology informs many successful serialized entertainment-education programs, notably the award-winning transmedia production East Los High.

The Sabido Methodology effectively targets both subconscious and conscious processing, creating multiple psychological access points to enter and emotionally engage with the story. Unlike today’s producers, however, Sabido did not have to contend with a complex transmedia structure and the challenge of maintaining narrative immersion across media.

Structuring the Narrative Zone

Several factors enable or dissuade audience engagement and migration. The theories of flow and narrative transportation can be used in conjunction with the Triune Brain theory to conceptualize a narrative zone. The narrative zone serves as a guide to strategic decision making and navigating the tensions to achieve immersion and motivation.

Optimal Engagement: The Theory of Flow

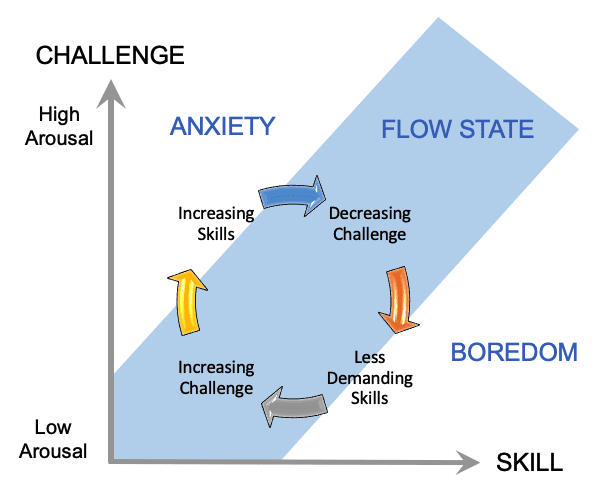

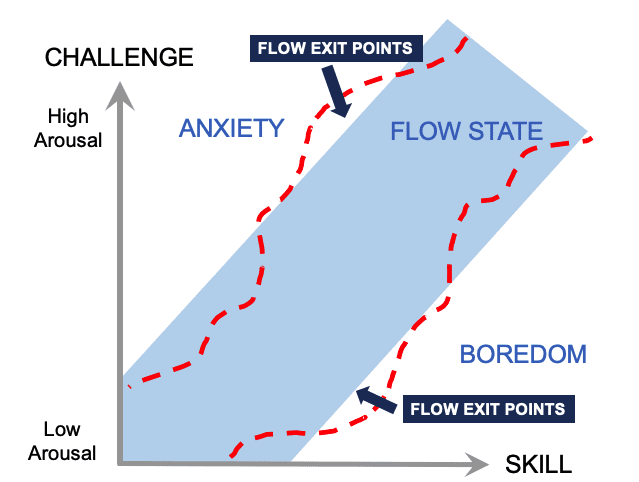

Flow is the state of optimal engagement where the challenge of an activity matches the skills of the user. It is a continual balancing act between effort and concentration within the boundaries of the user’s capabilities (Csikszentmihalyi 1991). Achieving flow results in a sense of deep enjoyment. Flow is defined as focused concentration on the activity with clear goals and feedback, with a sense of control and a loss of self-consciousness and time. Maintaining flow requires continually offsetting challenge with the requisite skill level. If the challenge is greater than the skill, anxiety results; if the skill is greater than the challenge, the individual becomes bored and disinterested. Optimal experience is not a steady state, but an evolving process of skill matching challenge through increasing and decreasing difficulty levels and opportunities for skill-building and mastery. The flow theory is applied to the development and analysis of gameplay, user experience, creative endeavors and other activities with intentional concentration (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flow theory combined with Triune Brain theory provides a useful heuristic to evaluate user experience as an ebb and flow of challenge and emotion that sustains engagement.

In a transmedia strategy, the triune brain model can be used to operationalize the theory of optimal experience where the flow zone must extend across media. Independent of the narrative experience, migration requires energy expenditure, whether following a link or looking for hidden clues. The levels of challenge and arousal in the necessary activities must maintain attention and interest. This cognitive cost must be commensurate with the audience member’s ability to achieve the gain. The actions necessary to reach the next entry point must not only promise visible reward, but they must support the unconscious perceptions of self-efficacy and positive emotion that fuel motivation. The triune brain model translates flow into instinct: a balance between threat and reward, avoid and approach. An activity must be challenging enough to achieve arousal and get the attention of the instinctive brain, but it must not surpass ability, creating threat. When the skill and challenge equilibrium work within the zone, it enhances self-efficacy and triggers the dopaminergic reward system which bolsters identity and self-esteem at the conscious level. Challenges that overwhelm skills threaten identity and self-competence, are translated physically into a threat response triggering the hypothalamic-pituitary adrenal axis resulting in cortisol release. This physical manifestation is consciously interpreted as anxiety, dislike, anger or frustration (Gregory and Rutledge 2016).

Research shows that staying in the flow zone increases positive affect; positive emotions increase motivation by inhibiting cognitive dissonance and increasing optimism and resilience (Fredrickson 2004). Negative experiences create a cognitive challenge to individual identity and can have a halo-effect, influencing the global opinion of a media property. Feelings of incompetence create cognitive dissonance and trigger the need to preserve or restore a positive sense of identity. To restore self-esteem and ego consonance, a person frequently attributes the negative affect to some aspect of the related experience (Elliot et al. 1994). In transmedia, challenges and cognitive dissonance that disrupt the ease of movement during migration create flow exit points, resulting in the potential loss of interest, the falling “out” of the story, and a lapse of motivation to continue exploring the storyworld (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Transmedia experiences require effort on the part of the audience to follow the story. Therefore, exit points undermine the commitment to continue and can result in complete loss of audience engagement.

The greater the amount of cognitive and emotional investment in successfully meeting a challenge or task, the more absorbing it becomes. In flow theory, optimal engagement occurs when all available energy and skills are devoted to an activity (Nakamura and Csikszentmihalyi 2002). This implies that a flow-inducing activity must be responsive to and designed to account for player cognition and incorporate a range of emotional and perceptual limits.

Narrative Transportation

Transporting into a narrative is phenomenologically similar to flow in that it results in complete absorption. Where flow speaks to the emotional experience of being within a transmedia structure so that movement across texts is seamless, the narrative zone addresses a larger, more meaning-based and subjective experience. Flow involves smooth, uninterrupted focus on an activity. By contrast, narrative immersion is the fluency of imagining which results in the ease of processing and a redirection of attention away from conscious awareness of surroundings or tasks and into the narrative (Busselle and Bilandzic 2008).

The flow state is often equated to narrative immersion with similar impact on subjective experience. However, in Triune Brain framework, flow is a new brain activity undertaken with intention, such as seeking out a companion social media site to a video series or following a link from one text to the next. Narrative actively engages all levels of the brain, but relies primarily on the engagement of old brain responses of emotion, visualization and instinct prior to processing and meaning-making in the new brain.

Stories are holistic and as such, replicate authentic human experiences. The brain’s instinctive ability to project and visualize create the sense of presence and transportation. Narratives activate neural mechanisms creating genuine physical responses and emotions. These nonverbal impressions are translated into conscious meaning.

Similar to the flow zone, immersion in a story creates a narrative zone that is a balance of tension and release through the relational investments in characters and plot. It also inhibits cognitive challenge, thereby increasing the motivation to pursue further opportunities for relationships and being part of the characters’ world. Crossing platforms breaks the fourth wall and challenges traditional mental schemas of entertainment narratives. These moments are vulnerable to narrative breaks where the audience loses the sense of immersion and psychologically falls out of the story. When moving to social media platforms, the powerful allure of personal relationships creates an emotional thread that can bridge the gap as long as signposts make the transition clear and the gap is cognitively narrow. Social media maintains the commitment to the narrative by moving the story into the audience’s personal space, engaging and impacting identity, emotion and beliefs.

The narrative zone defines the storyworld. There are three main components necessary for traveling in a storyworld: 1) cognitive engagement, 2) emotional engagement and 3) mental imagery. These correspond to the functional breakdown of the three processing centers of the Triune Brain theory. It is the mutually-reinforcing combination of the cognition, emotion and visualization that produces the experience of narrative transportation. Every within-narrative input, or audience interaction within the storyworld, amplifies the experience, whether it is exchanging Tweets with Gigi from Lizzie Bennet Diaries or posting comments to the pregnant teen Ceci’s vlogs in East Los High. For example, applying the Triune Brain theory explains how the physical interaction with characters increases the drive to maintain connection due to the instinctive motivation to protect against the emotional loss of social disconnection.

In a transmedia story, the audience becomes the traveler, moving into and across a storyworld. While the narrative determines the traveler’s role and identity, the platforms, with their distinct social norms and affordances, function as both context and content. Each platform creates a distinctive embodied experience and frames cognitive meaning.

The brain’s power of projection and imaging can overcome any emotional distancing from migration as long as the content and platform are appropriately matched so that context and content are true to the canon psychologically as well as factually. When the story maintains internal integrity, active identification and imagination allow the audience to psychologically adapts to the logic and laws of the narrative world across media. While the narrative zone becomes more porous during migration, transmedia uniquely enables transformation from audience to stakeholder when the traveler takes ownership of the narrative and the journey, making it is no longer the property of the storyteller alone.

Ownership shifts the audience mindset, amplifying the commitment to immersion as the narrative becomes intertwined with identity and self-efficacy. This enhances persuasion through the disinhibition of critical thinking functions accompanied by heightened emotional responses and amplified self-focus. Research shows that audience members who imagined themselves as the “star” of a narrative had stronger emotional responses and reported a more positive experience (Escalas 2007).

Media and Platform Choices Matter

Platform brand and message congruence is an opportunity to maximize message impact and story continuity. The differential impact of a common message across various media shows that the communication medium frames message perception. People have medium-specific cognitive processing strategies and social expectations, focusing on content type related to the source. Identical content is perceived differently depending on the platform. For example, content on Facebook was seen as having more personality (Walsh et al. 2013). Political messages on Twitter increased the consumers’ sense of connection to the politician and the consumer’s ability to become immersed in the narrative compared to identical messages delivered in a newspaper (Lee and Shin 2014).

Unconscious expectations and beliefs about any given medium affect how people manage their social contacts and communications strategies. This includes content-creation and interaction, independent of the message. Viewer-held assumptions about source influence the perceptions of information credibility, relevance and potential for enjoyment (Coe et al. 2008). Consequently, to avoid narrative exit points and maximize experience, content must align with the platform brand personality and social norms.

Cost Benefit Analysis

People run a cognitive cost/benefit analysis in the face of any decision or behavior change, including migrating across media. The costs and benefits can be broken down into categories of subjective evaluation and unconscious responses that manifest in observed behaviors and attitudes. These include beliefs and expectations about:

- Success, such as feelings about one’s abilities, competence, and potential for attainment.

- The intrinsic value of the action, such as the enjoyment from the balance between stimulation and control, the act of performing a deed or the opportunity to play.

- Usefulness, such as longer-term goal achievement, skill-building or learning.

- Perceived or actual costs, such as investment of time, money, identity or the loss of other opportunities.

- Potential for social connection and affiliation with desired or undesired groups or identities.

These factors can influence motivation for migration across transmedia texts independent of story quality or creativity. The audience wants as few costs as possible to achieve their goals. An audience-centric perspective looks through the audience’s eyes to understand their goals and see the potential obstacles that may hinder experience or conflict with outcome.

Conclusion

The continuing shifts in the media landscape and the increasing menu of media tools and platforms demand a better understanding of the psychological implications of content, structural choices and their interaction. This is particularly true of the complex mix of story and strategic decisions necessary to create a larger, more meaningful and impactful experience in transmedia storytelling. Integrating a psychological framework enables an audience-centric approach to experience building. It integrates the audience’s beliefs, values and goals and highlights the underpinnings of individual preferences, meaning-making and decision-making processes. Theories translated into actionable, audience-centric guidelines give storytellers, designers and producers another dimension in which to conceptualize their decisions and keep the audience engaged in the narrative zone. The competition for the audience’s attention will continue to grow as technology evolves. Being an early adopter of the “next new thing” is not a sustainable strategy. Applying psychology is, however, because fundamental human goals and needs remain constant. This knowledge allows producers to get in front of trends and anticipate how new technologies and approaches can satisfy the audience while minimizing resistance. Integrating psychology will enable a more purposeful intersection of story, structure and audience to unleash the creativity and innovation that fuels a successful transmedia practice.

References

Barasch, Alixandra, Kristin Diehl, and Gal Zauberman. 2014. “When Happiness Shared Is Happiness Halved: How Taking Photos to Share With Others Affects Experiences and Memories.” Advances in Consumer Research 42: 101–105.

Bruner, Jerome. 1991. “The Narrative Construction of Reality.” Critical Inquiry 18 (1): 1–21.

Busselle, Rick, and Helena Bilandzic. 2008. “Fictionality and Perceived Realism in Experiencing Stories: A Model of Narrative Comprehension and Engagement.” Communication Theory 18 (2): 255–280.

Cialdini, Robert B. 2007. Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion. Revised ed. New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers.

Coe, Kevin, David Tewksbury, Bradley J. Bond, Kristin L. Drogos, Robert W. Porter, Ashley Yahn, and Yuanyuan Zhang. 2008. “Hostile News: Partisan Use and Perceptions of Cable News Programming.” Journal of Communication 58 (2): 201–219.

Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. 1991. Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. New York, NY: HarperCollins Publishers.

Dalbert, Claudia. 2004. “The World is More Just for Me than Generally: About the Personal Belief in a Just World Scale’s Validity.” Social Justice Research 12 (2): 79–98.

Douglas, J. Yellowlees, and Andrew B. Hargadon. 2001. “The Pleasures of Immersion and Engagement: Schemas, Scripts and the Fifth Business.” Digital Creativity 12 (3): 153–166.

Elliot, Andrew J., Holly A. McGregor, Shelly Gable, and Patricia G. Devine. 1994. “On the Motivational Nature of Cognitive Dissonance: Dissonance as Psychological Comfort.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 67 (3): 382–394.

Escalas, Jennifer Edson. 2007. “Self-Referencing and Persuasion: Narrative Transportation versus Analytical Elaboration.” Journal of Consumer Research 33: 421–429.

Fredrickson, Barbara L. 2004. “The Broaden-and-Build Theory of Positive Emotions.” Philosophical Transactions Royal Society London 359: 1367–1377.

Gerrig, Richard J. 1993. Experiencing Narrative Worlds: On the Psychological Activities of Reading. New Haven, CT: Westview.

Green, Melanie C., and Timothy C. Brock. 2002. “In the Mind’s Eye: Transportation-imagery Model of Narrative Persuasion.” In Narrative Impact: Social and Cognitive Foundations, edited by Melanie C. Green, Jeffrey J. Strange, and Timothy C. Brock, 315–342. Mahwah, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Gregory, Erik M., and Pamela Rutledge. 2016. Exploring Positive Psychology: The Science of Happiness and Well-Being. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-Clio Praeger.

Haven, Kendall. 2007. Story Proof: The Science Behind the Startlng Power of Story. Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited.

Horton, Donald, and R. Richard Wohl. 1956. “Mass Communication and Para-social Interaction.” Psychiatry 19: 215–219.

Lee, Eun Ju, and Soo Yun Shin. 2014. “When the Medium Is the Message: How Transportability Moderates the Effects of Politicians’ Twitter Communication.” Communication Research 41 (8): 1088–1110.

Lieberman, Matthew D. 2013. Social: Why Our Brains are Wired to Connect. New York, NY: Crown Publishers.

MacLean, Paul D. 1990. The Triune Brain in Evolution. New York, NY: Plenum Press.

Mark, Margaret, and Carol S. Pearson. 2001. The Hero and the Outlaw: Building Extraordinary Brands Through the Power of Archetypes. New York, NY: McGraw Hill.

McAdams, Dan P. 2013. “The Psychological Self as Actor, Agent, and Author.” Perspectives on Psychological Science 8 (3): 272–295.

Nakamura, Jeanne, and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. 2002. “The Construction of Meaning through Vital Engagement.” In Flourishing:Positive Psychology and the Live Well-Lived, edited by Corey L. M. Keyes and Jonathan Haidt, 83–104. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

O’Connor, Zena. 2015. “Colour, Contrast and Gestalt Theories of Perception: The Impact in Contemporary Visual Communications Design.” Color Research & Application 40 (1): 85–92. doi: 10.1002/col.21858.

Papa, Michael J, Arvind Singhal, Sweety Law, Saumya Pant, Suruchi Sood, Everett M. Rogers, and Corinne L. Shefner‐Rogers. 2000. “Entertainment‐education and Social Change: An Analysis of Parasocial Interaction, Social Learning, Collective Efficacy, and Paradoxical Communication.” Journal of Communication 50 (4): 31–55.

Petrie, Helen, and Nigel Bevan. 2009. “The Evaluation of Accessibility, Usability and User Experience.” In The Universal Access Handbook, edited by Constantine Stepanidis, 1–30. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Phillips, Andrea. 2012. A Creator’s Guide to Transmedia Storytelling. New York, NY: McGraw Hill.

Read, Herbert, Michael Fordham, and Gerhard Adler. eds. 1959/2014. C.G. Jung: The Collected Works—The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. Second ed. Vol. 9. New York, NY: Routledge.

Reiner, Anton. 1990. “An Explanation of Behavior: The Triune Brain in Evolution.” Science 250 (4978): 303–305.

Rutledge, Pamela. 2012. “Augmented Reality: Brain-based Persuasion Model.” 2012 EEE International Conference on e-Learning, e-Business, Enterprise Information Systems, and e-Government, Las Vegas, NV, July 16-19.

Singhal, Arvind, Rafael Obregon, and Everett M. Rogers. 1995. “Reconstructing the Story of Simplemente Maria, the Most Popular Telenovela in Latin America of All Time.” International Communication Gazette 54 (1): 1–15.

Teixeira, Thales, Michel Wedel, and Rik Pieters. 2012. “Emotion-induced Engagement in Internet Video Advertisements.” Journal of Marketing Research 49 (2): 144–159.

Walsh, Patrick, Galen Clavio, M. David Lovell, and Matthew Blaszka. 2013. “Differences in Event Brand Personality Between Social Media Users and Non-users.” Sport Marketing Quarterly 22 (4): 214–223.

Woodside, Arch G., Suresh Sood, and Kenneth E. Miller. 2008. “When Consumers and Brands Talk: Storytelling Theory and Research in Psychology and Marketing.” Psychology & Marketing 25 (2): 103–145.

Zillmann, Dolf, and Peter Vorderer. 2000. Media Entertainment: The Psychology of its Appeal. Mahwaw, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Comments are closed.